1789 AND ALL THAT

In case anyone's failed to notice, this year marks the 200th anniversary of the 'French Revolution'. This is usually seen as a series of political and social events beginning with the storming of the Bastille in July 1789 and culminating in the declaration of the Republic in September 1792 ('Year 1'), or perhaps Napoleon's seizure of power in 1799, depending on the political complexion of the historian involved.

The significance of (some, carefully chosen, of) these events for the bourgeoisie is quite clear - it was during this period that the French nation was created. This was an event which inspired nation-building bourgeois across the world. It is no coincidence that so many nations use some kind of tricolour as their national emblem. What the anniversary celebrators don't want us to think about is that every nation can only exist in so far as the class struggle can be suppressed. Most of the world's nations claim to have been brought into existence by some kind of 'revolution' which overthrew an evil and corrupt 'ancien regime'. Frequently the 'revolution' is just a coup d'etat or institutional rearrangement, but often it is a bloody counter-revolution. Every new-born nation must be baptised in working class blood, and France was no exception.

The purpose of this article is to make clear that the proletariat has always had to fight independently for its interests against the bourgeoisie. It is not a question of whether or not communism was possible. Even if it is not possible to create communism, proletarians still have an interest in having enough to eat and not being massacred in wars. 'Progress' for the bourgeoisie has never meant improvements for the proletariat. It has simply meant a more rapid numerical growth of the proletariat and the further development of exploitation, starvation and war.

For leftie historians the working class progresses from 'apolitical' food riots to the modern labour movement and universal suffrage. For theorists of capitalist decadence, including Karl Marx, the working class had to support various fractions of the bourgeoisie in the creation of nation states while capital was in its ascendant phase. Against both of these positions we assert the 'Invariant Programme' of rioting, looting, machine-breaking, resistance to work and insurrection against all states.

ARISTOCRATS vs. BOURGEOIS?

We must start off by completely rejecting the notion that the two sections of the ruling class who fought over possession of the State were two separate classes - the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie. That is, we reject the notion that France between 1789 and 1793 underwent a 'bourgeois revolution'.

The bourgeoisie did not need political revolutions to establish its domination over society since it was able to establish its mode of production side by side with the old feudal system. The feudal system was not so much overthrown as 'corrupted' from within by the gradual development of trade, money-lending and the beginnings of industry in the cities. As early as the 16th century the Absolute Monarchs of Europe were no longer feudal kings but bourgeois who fought their wars and ran their State bureaucracies not on the basis of feudal service and loyalties but on the basis of money. As a result, they were either heavily in debt or themselves became money-lenders, like the Pope.

When the 'bourgeois revolutionaries' in France started flogging off the church lands and monasteries in 1789 they were only doing what Henry VIII had done in England two and a half centuries earlier.

What is also important is that on the eve of 1789 the French ruling class was NOT divided into an 'aristocratic' land-owning and church camp and a party of 'bourgeois' industrialists and merchants. The expansion of capitalist enterprise (whether overseas trading or industry) was carried on by nobles as much as by the 'bourgeois' nouveaux riches. At the same time, many non-nobles preferred to invest their capital in land, titles and government stock. So many ennobling offices were for sale that anyone with enough money could join the nobility. A particularly cushy number was the position of 'King's Secretary', a sinecure which conferred hereditary nobility on the purchaser and his family, a snip at 150,000 livres. On the ideological level, the 'Enlightenment' was as much a product of the liberal nobility as of any other bourgeois fraction.

The involvement of nobles in 'Revolutionary' politics cannot be ignored. It was the Comte de Mirabeau who emerged as the leader of the National Assembly (the parliament formed in June 1789), it was the Marquis de Lafayette who became the first commander of the Paris National Guard, it was the Vicomte de Noailles who introduced the decrees proposing the 'abolition of feudalism' on 4 August 1789, and it was Talleyrand (a bishop!) who proposed the selling off of church land.

CLASSES AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS

If the feudal nobility did not exist as a class, the proletariat certainly did, and may even have been a majority of the population.

In 1789, France was second only to England as an industrial country, large manufactories promoted by the State had already appeared. Real industrialisation had not yet begun, though. In 1789 Great Britain had 200 mills on the Arkwright model. France had eight. There were no factory towns and no modern industrial proletariat.

In most of the country industry was still largely carried on in cottages, or by master craftsmen and their journeymen in small medieval city workshops. But the old guilds had declined and no longer protected the journeymen who were becoming reduced to the status of wage earners with little chance of ever becoming masters. The smaller masters were also being proletarianised as their interests separated from those of the merchant manufacturers.

The fabled 'sans-culottes' of the Paris faubourgs (poor districts) were by no means exclusively proletarian, they included small shopkeepers and artisans, but it was undoubtedly the proletarian majority which gave the specific character to 'sans-culotte' struggles.

The overwhelming majority' of the French population (around 85%, of 23 million) lived in the countryside. Undoubtedly many were petty bourgeois peasants - that is peasants who have an interest in high food prices. Many more, though, were either poor peasants, (that is, peasants who were well on the way to proletarianisation, such as sharecroppers) or simply rural proletarians ('landless labourers'). Many of these were destitute : in 1777 over a million people were officially declared to be beggars. Many peasants still relied on pre-capitalist forms of land ownership and village organisation for their, survival. All this meant that the content of struggles in the countryside was very confused, with the struggle of the proletariat frequently being mixed up with 'kulak' struggles or the struggle to defend pre-capitalist conditions.

The peasants were no longer serfs, although on the royal lands serfdom had only been abolished as late as 1779. Statute labour, however, still existed and took on an enormous variety of forms: work in the Lord's fields, work in his parks and gardens... There were also a bewildering array of taxes to be paid, in addition to land-rent. The peasant paid for the right of marriage, baptism, burial; he paid on everything he bought or sold. As the position of the land-owners declined their extraction of 'feudal' dues became all the more rapacious as it was the only way they could maintain their profits.

A whole new profession of lawyers had come into being, the 'feudists', whose job was to help the land-owners revive old feudal obligations and maximise existing ones. Not surprisingly, revolts by the peasantry took the form of refusals to pay some or all of these exactions.

All sections of the proletariat were precariously dependent on the price of bread which could fluctuate wildly depending on the state of the harvest. Hardly a year passed without some part of France being plunged into famine conditions. High points in the class struggle tended to correspond to bad harvests across the whole country, e.g. 1788.

The struggle often took the form of attempts to force reductions in the price of bread and other necessities by collective force ('taxation populaire'). Typically people would invade the flour markets and besiege bakers' shops forcing dealers to sell the goods at a 'just' price.

A particularly widespread example of this was the 'flour war' of April-May 1775 which gripped Paris and its neighbouring provinces for over a fortnight and caused panic in the Court. It spread into Paris itself and resulted in the siege of every baker's shop in the city centre and the inner faubourgs. The movement was only crushed by the massive use of troops and hundreds of arrests.

Similar outbreaks of 'taxation populaire' continued during the 'Revolution' period, in 1789, 1792-3 and 1795. The target of these movements was the prosperous peasant, the grain merchant, miller or baker. Whether the bourgeois in question supported the old or the new regime was unimportant.

The immediate cause of the political crisis in the State was the enormous debt created by France's participation in the American War of Independence. Half the state's revenue was being used to pay interest on loans.

On Feb 22, 1787 the Assembly of Notables was convened at Versailles. This was an obscure aristocratic body which had not met since 1626. Nothing was decided, all that happened is that it became public knowledge that the national debt had reached 1.5 thousand million livres. This was an incredible figure.

On Aug 8, 1788 Louis XVI was obliged to convene the Estates General and to fix the opening for May 1, 1789. This body had not met since 1614 but was different in that it was elected and was supposed to represent the three 'Orders' of society - the Clergy, the Nobility and the so-called Third Estate. The Third Estate was what in Britain would be called the Commons. That is, in theory, everyone else, in practice, the non-aristocratic bourgeoisie. The elections were indirect but nevertheless provided an opportunity for the radical bourgeois to propagate their program and ideology throughout the whole of society.

It was increasingly necessary to channel working class discontent into support for reforms since things had already reached the stage where any disorder on the streets of Paris risked turning into a proletarian rising. For example, the magistrates of the 'parlement' (Courts of Justice) of Paris got themselves exiled to the provinces on two occasions (1787, 1788) for being mildly critical of the Court. Their first return resulted in a few disorderly celebrations by lawyers clerks and university students but on the second occasion they were joined by proles from the faubourgs, resulting in violent rioting in which guard posts were looted and burned.

A week before the Estates General was to meet, the famous Reveillon riots broke out when the Electoral Assembly meetings were held in Paris. At one of these meetings a paper manufacturer by the name of Reveillon (together with another called Henriot) made a particularly offensive speech to the assembled proles. He said that wages in industry were too high. The reaction was swift, an effigy of Reveillon was hung in the Place de la Greve and Henriot's house was burnt down. The next day a crowd went to Reveillon's factory and made the workers stop work. Then they plundered the warehouse. Much fighting with troops ensued and Reveillon's house was burnt down that evening. A few days later a mob tried to storm the Bicetre prison. Even during this movement, which was clearly for proletarian interests, a bourgeois political influence was emerging. Insurgents shouted 'Long live the Third Estate' and 'Liberty... No Surrender'.

THE COUNTRYSIDE

Meanwhile the inhabitants of the countryside had not been idle. Starting in December 1788, there was a massive movement of attacks on grain boats and granaries; assaults on customs officials and merchants; 'taxation populaire' of bread and wheat; and widespread destruction of bourgeois property. This occurred in virtually every province. North of Paris the starving rural poor attacked the game laws and hunting rights of the nobility by indulging in unrestrained poaching.

In the spring of 1789, after lying dormant for almost a century, peasant anger against royal taxes and seigneurial dues began to be expressed explosively all over the country. The peasants burned the chateaux and with them the hated manorial rolls on which were inscribed the details of the dues and obligations. It was this which caused the National Assembly to issue its decrees of August 4 and 5 which abolished, or in most cases made redeemable into money, all seigneurial burdens on the peasantry. The peasants, however, carried on refusing to pay anything. Three years later the Jacobin government had to annul the peasant debt.

MOB RULE

Some six weeks after the opening of the Estates General, the Third Estate constituted themselves and all who were prepared to join them as the National Assembly with the right to recast the constitution. The response of the Court was to gather troops to invade Paris and dissolve the National Assembly (still based at Versailles). This led to the first of many popular calls to arms. On July 12 crowds gathered in the gardens of the Palais Royal, the home of the Duc d'Orleans (whom many radical bourgeois wanted to place on the throne) to hear 'patriotic' orators. Marchers paraded along the boulevards and Besenval, the commander of the Paris garrison, withdrew to the Champ de Mars, leaving the capital in the hands of the insurgents. They proceeded to destroy the 'barrieres', or customs posts, ringing the city. These were despised because of the tolls they imposed on food and wine entering the city.

Men armed with pikes and cudgels spread themselves through every quarter, knocking at the doors of the rich to demand money and arms. Gunsmiths' shops were looted and pikes began to be forged in the faubourgs. The next day the monastery of the St. Lazare brotherhood was broken into, looted, searched for arms and grain, and its prisoners were released. Fifty two carts laden with flour were dragged to the Halles for free distribution.

In many ways the actions of the masses were similar to the glorious few days of 'mob rule' which had shaken British capitalism nine years earlier in the London 'Gordon Riots' in which half a dozen prisons were completely destroyed and the homes of the rich pillaged and burnt on a massive scale.

There were the same mass releases of prisoners, for example - not just 'political' ones, either. In Paris, however, the movement was nowhere near as extreme - 'Nothing was touched that day, either at the Treasury or the Bank' said the British ambassador. This was partly because the bourgeoisie were better organised to control things. The patriotic bourgeoisie formed a provisional city government based at the Hotel de Ville (City Hall). Thoroughly alarmed by what was happening, they began to enroll a citizen's militia (the National Guard) to uphold bourgeois order. On the 13th the debtors' prison of La Force was seized and all the prisoners released, but an attempt to free prisoners from Chatelet prison on the same day was crushed by the National Guard. It is also known that around the same time the National Guard carried out several night-time summary executions of looters. They challenged passers-by with the words 'Are you for the Nation?'. Shortly afterwards, similar militias were formed all over the country to fight the insurgent peasants and rural proles.

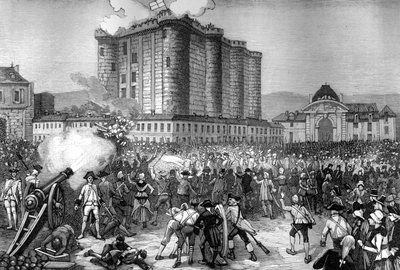

THE BASTILLE FALLS...

The insurgents continued the search for arms and ammunition and this was one of the main reasons why the Bastille Fortress was attacked on 14th, this and its strategic military importance (rather than because It was a 'symbol of Absolutism'). They were short of powder and it was known that large stocks existed in the Bastille. At the same time its guns were trained ominously on the St. Antoine faubourg. So, after 30,000 muskets had been removed from the Hotel des Invalides across the river, the cry went up 'To the Bastille!'. After much fruitless negotiation between City Hall and the Bastille's governor, the impatient crowd took the place by storm at the cost of 150 lives. These the governor, the Marquis de Launay, paid for when he was dragged away from his bourgeois protectors outside City Hall and beheaded in the street.

The Bastille's surrender had remarkable political results. The National Assembly was saved and received royal blessing. Many Court supporters fled the country, or tried to. Among these was the notorious grain speculator Foulon who was dragged back to Paris and hung from a lamp post by the angry mob. In Paris, power passed into the hands of the Committee of Electors, who set up a city council (the Commune). The King himself came to Paris wearing the red, white and blue cockade of the patriots. But he continued to plot against the Assembly and in October once again tried to end the situation of bourgeois dual power by a show of force. The Flanders regiment and the dragoons were called to Versailles.

Once again the patriots called on the masses to save them, but this time things were more under control. Leading patriots like Danton, Marat and Loustalot had been inciting a march to Versailles for some time. On Oct 5 a crowd of working class women marched to City Hall and forced open the doors demanding. bread and arms. They were quickly enroled under suitable leadership. The patriots had again managed to divert class hatred away from themselves onto the wicked aristos. Later on, men began to march as well, and, a few hours later, were followed by the National Guard to prevent any mishaps. The National Guard arrived at the Palace just in time to save the royals from the mob and the king was brought to Paris as a virtual prisoner. The constitutional monarchy was firmly established.

The bourgeoisie could now return to the problem of the proles. The Paris municipality, using the excuse of the killing of a baker on Oct 21, went to the Assembly to beg for martial law. It was voted for at once.

The new regime was not simply based on force, however. Despite the notorious division of citizens into 'active' (propertied) and 'passive' categories and the gradual erosion of democratic rights throughout 1790, there remained a high level of participation in the State. This occurred through the local government bodies known as Communes which were composed of smaller 'districts' or 'sections' based on regular general assemblies. The districts played an important role: they appointed magistrates, organised the National Guard and armed 'the people' for patriotic purposes. It was by means of these bodies that bourgeois orators such as Danton and Marat were able to gain such an influence. In addition, numerous Clubs and 'fraternal' societies were formed which after 1790 opened their doors to wage-earners and craftsmen.

... THE CLASS STRUGGLE CONTINUES

But while the bourgeoisie carried out their great program of modernising the State, the working class never completely abandoned its struggle, particularly as inflation and food shortages began to bite again in mid 1791.

In Paris there was a large scale strike movement for higher wages which began amongst journeymen carpenters and quickly spread to other cities. The City Council condemned their strike as illegal and rejected their demand for a minimum wage as contrary to liberal principles. But they dared not use too much repression in case the movement spread. Their fears were well grounded. In June the master blacksmiths, in a petition to the assembly, warned of the existence of a 'general coalition' of 80,000 workers including joiners, cobblers and locksmiths as well as their own journeymen. The Assembly responded by passing the notorious Le Chapelier Law which declared all workers' associations of any kind to be illegal. It was to remain on the statute book for almost a century.

In August 1791 food riots again convulsed the whole country, lasting until April the following year.

FROM CHATTEL SLAVES TO WAGE SLAVES

On 22 August 1791, the slaves of San Domingo (now Haiti) revolted. Each slave-gang killed its masters and set the plantation on fire. Within a few days, half of the North Plain - the most important sugar and coffee growing area in the French empire - was a flaming ruin. The revolt quickly spread to maroons (escaped slaves living in the hills) and poorer mulattos (people of mixed race). It was to lead to a many-sided war that eventually forced the Convention to agree to the abolition of slavery in the colony in Feb. 1794. This was done to encourage the slaves to fight for France against Britain which had declared war on France at the beginning of 1793.

As with the class struggle in France, the revolt had quickly acquired a bourgeois leadership just as steeped in the ideas of Liberty and Equality as their class brothers in Paris and Marseilles. The most famous of these was Toussaint Breda (later "L'Ouverture"), a "senior executive" amongst slaves who had organised the labour of several hundred others and had originally protected his master's property from destruction. When this stratum finally came to power they did everything they could to rebuild the sugar economy and keep the old plantation owners in place (as later Lenin would strive to keep the old factory bosses). A savage code of labour discipline was enforced against considerable resistance from the ex-slaves who said "moin pas esclave, moin pas travaye" - "I'm no slave, I won't work".

In Paris in January 1792 the shortage of sugar and other colonial products caused by the slave revolt in San Domingo caused price fixing riots to break out in various parts of the city. In February there were similar riots in which cart loads of sugar were seized even though they were under military escort. The struggle of the slaves had found an international echo!

THE WAR

In April 1792 the government of the Girondins (moderate republicans) declared war on Austria. This was partly necessitated by the fact that the French noble emigres were plotting with Austria, Prussia, and the German Princes to invade France and re-establish the Old Regime. It was also a good way of creating national unity. Early defeats in the war brought radicalisation, in a purely bourgeois republican sense. In August and September the monarchy was finally overthrown and the republic established. The parliament underwent another metamorphosis, this time into the National Convention. The distinction between active and passive citizens was abolished. The King got the chop.

The French army was ineffective and still staffed by royalist officers. Dumouriez, the Republic's leading general was shortly to desert to the enemy. Only unprecedented and extreme methods could win the war. The nation's resources were mobilised through conscription, rationing, a rigidly controlled war economy and the virtual abolition of the distinction between soldiers and civilians. By March 1793 France was at war with most of Europe: and had begun annexations (France was entitled to her 'natural frontiers'). In June the Convention decreed the 'levee en masse', which called up three quarters of a million men. Shortly before this, the Girondins were overthrown after finding themselves increasingly out-manoeuvred by the Jacobins who alone had the popular support to win the war.

The war dramatically worsened conditions of life for the poor. In November 1792 a new and more extensive movement against food prices began spreading to eight departments, starting amongst foresters, craftsmen and glass factory workers in Sarthe who raided the local markets under arms. In many regions prices were forced down and the National Guard were powerless to intervene. In others, the local National Guard even joined the movement (out in the styx they were less loyal and petty bourgeois than in Paris!).

In Feb. 1793 Paris was shaken by a far larger price reduction movement than the one a year,earlier. It lasted only one day but affected all 48 Parisian sections, taking the form of a mass invasion of grocers' and chandlers' shops. Barere, on the Committee of Public Safety, spoke darkly of 'aristocrats in disguise' and insisted that such luxuries as sugar and coffee were unlikely objects of popular passion.

These struggles, together with the demands of the war economy, were instrumental in forcing the convention to pass the law of the General Maximum of Sept. 29, 1793. They were also encouraged by a massive demonstration of sans-culottes who, on Sept. 5, went to the convention accompanied by the left wing municipal leaders Roux and Hebert to demand price controls. This law imposed a ceiling on the prices of most commodities of prime necessity, as well as labour power. This led to an important strike movement in Paris in the summer of 1794.

THE END

In many agricultural districts the law was applied far more vigorously to wages than to prices. In Paris it tended to be the other way round at first because of the strength of the class struggle. War production meant that labour was scarce so workers frequently had to be paid higher than legal rates despite restrictions on labour mobility. But the price controls began to be relaxed in March 1794 and more and more groups of workers began to press wage demands. In June the arms workers struck and soon the movement spread to building workers, potters and government employees. On July 7, even the Committee of Public Safety's printers went on strike. In the midst of all this the Paris Commune published new wage rates strictly in line with the law, obliging many workers to take a 50% pay cut.

At the same time the bourgeoisie as a whole were dispensing with the Jacobins who had outlived their usefulness (the war was over). Robespierre and his associates were expelled from the convention and arrested. Having temporarily escaped they took refuge in the City Hall. On the same day it was besieged by angry workers. The sans-culottes could no longer be roused to support the left against the right and jeered the councillors of the Commune as they were led off to be guillotined.

At first the workers were allowed decent pay rises but these were quickly eaten up by inflation as free market conditions returned. The closure of government workshops led to a rise in unemployment.

The sans-culottes attempted to rise for the last time in May 1795 with a massive political and military demonstration marching on the convention to press their demands, which were as confused as ever. The most popular slogan was 'Bread and the Constitution of 1793'. But this time the bourgeoisie didn't have to give an inch because they were able to confront the marchers with a regular army loyal to the state. The insurgents gave in without firing a shot, so as to avoid bloodshed, and slunk back to their hovels. Savage reprisals followed. The days of mass struggle in France were over for another 35 years. The country was prepared for the massacres of the Napoleonic wars.

It was the war economy that had been the greatest achievement of the French bourgeoisie in the 'Revolutionary' years. They had layed the foundations for modern warfare, both as a means of carrying on capitalist competition and as a means of dealing with the proletariat, a class who were becoming everywhere more numerous and troublesome.